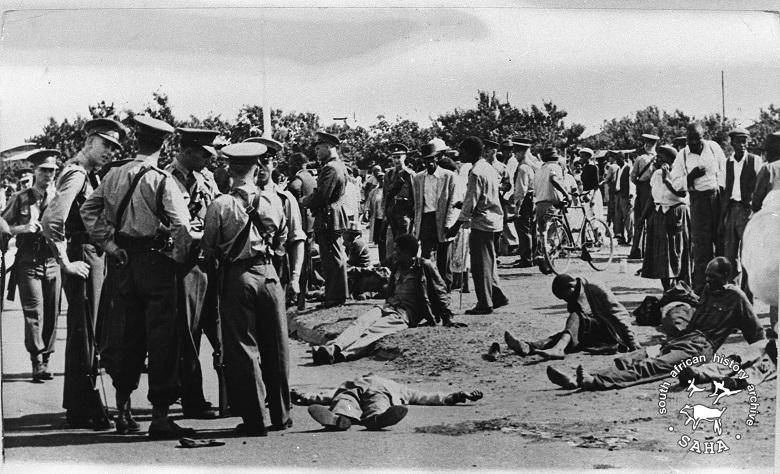

Both the ANC and the PAC were banned by the government in April 1960, following the massacre by police of 69 unarmed pass law protesters in Sharpeville. In the period that followed, it was the response to the challenge of underground conditions, more than the debate over non-racialism, that determined the level of mass support of the two organizations.

When the ANC called an 'All-in Conference' in May 1961 to draft a ‘non-racial democratic constitution for South Africa', the PAC opted out. When the ANC organized a national stay-at-home, the PAC distributed leaflets aimed at sabotaging the campaign. These actions did little to build mass support for the fledgling PAC. The ANC, on the other hand, was able to rely on its historical reputation to such an extent that the launch of the first organized military response to apartheid — identified only as being under the guidance of 'the national liberation movement'— was immediately embraced as a Congress initiative.

Units of Umkonto we Sizwe today carried out planned attacks against government installations, particularly those connected with the policy of apartheid and race discrimination. Umkhonto we Sizwe is a new,independent body, formed by Africans. It includes in its ranks South Africans of all races.

Umkhonto we Sizwe fully supports the national liberation movement and our members, jointly and individually, place themselves under the overallpolitical guidance of that movement. It is, however, well known that themain national liberation organizations in this country have consistentlyfollowed a policy of non-violence. But the people's patience is not endless.The time comes in the life of any nation when there remain only two choices: submit or fight. That time has now come to South Africa. We shall not submit, and we have no choice but to hit back by all means within our power in defence of our people, our future and our freedom.

We hope — even at this late hour — that our first actions will awaken everyone to a realization of the disastrous situation to which the Nationalist policy is leading. In these actions, we are working in the best interests of all the people of this country — black, brown and white — whose future happiness and well-being cannot be attained without the overthrow of the Nationalist government, the abolition of white supremacy, and the winning of liberty, democracy and full national rights and equality for all the people of this country.

Flyer issued by 'command of Umkhonto we Sizwe' (Spear of the Nation), 16 December 1961

“I was one of those they recruited to the armed struggle. Maybe it was because people heard that I was one of those who said, 'To hell with non-violent struggle!' and maybe openly talked of taking up arms. My immediate reaction was, 'Fantastic, Umkhonto has come up.' But we had become quite respectable leaders of the Indian community — what would the reaction in the Indian community be?

We debated the question of moving from the Gandhian philosophy — how would we justify our movement away from non-violence? But if one looks at the struggle from the turn of the century, you would find there's been a move all the way, there'd been a difference from Gandhi to my grandfather,and from my grandfather to my father, who was talking of more radical action.

We operated as an MK [Umkhonto] unit from 1961 right up to 1963. The reaction of our people during the sabotage campaign was that the debate became even more hotter. People were now looking to join MK. At the Rand Youth Club one Saturday evening, an activist raised the question and openly said, 'You know, it's time we all joined MK. You fellows still believe in your Gandhian philosophy and it's about time you abandoned it. You'll get nowhere.'

The units at that time were racially comprised, because it's easy to move around that way. I mean, two o'clock in the morning, if you find one African in the heart of Johannesburg riding around with three whites you already become suspicious, but when you find four Indians, there's less suspicion. We, as an Indian unit, had a much broader scope to work in.

We were amongst the very first MK cadres to be arrested. In April '63 we were the first MK guys to appear in court, and this had a tremendous influence amongst the Indian youth. People of all races filled the court, it was just impossible to move. I would say we had firmly established (1) the non-racial aspect of the struggle, and (2) the need to take up arms.”

INDRES NAIDOO, among the first Umkhonto we Sizwe recruits

“For me, it was a relief when Umkhonto we Sizwe was formed, because I'd been arguing for it amongst some groups of people I knew. Eventually whenI was asked to join Umkhonto we Sizwe at the time of its formation, I said yes,and the person who asked me said, ‘Go away and think about it.’ And I said, ‘But I've been arguing for it for over a year — what's there to think about?’

Were there any specific implications of you being one of the few whites in a largely black organization?

I think there were possibilities that developed because of my skills. That's where my training as an engineer was important, you see, because technical skills were in short supply — it's one of the effects of racism in South Africa.I was known amongst some of my comrades as 'Mr Technico' — I didn't mind getting my hands dirty, covered in ink and things like that, you see.When it came to buying duplicators, it was much easier for a white to go into a shop and buy a duplicator, or to buy hacksaws to cut iron tubes, or to buy a rope or whatever — it was just easier. And then there was always the question of access to cars, and time. Whites didn't have to work such long hours or travel so far, so you could do things. So in the facilitation sense, it helped.

I felt that that was what I could contribute, and I felt morally bound to contribute. Because we lived in white South Africa I got a university degree,and that was part of the privilege of being white. Once I understood that, it was necessary to give back that privilege. If you support the movement only,then you give it back in another way — you get rich quick and you pay conscience money. If you're in it you use your skills that you've got, as a result of your privileges, for that movement, in that movement. That was my approach to it, so I never resented it at all, never.

One of the bitternesses of prison was that we were deliberately kept away from our comrades. I was sentenced with seven other comrades — I could not see them from the day we were sentenced, because they are black and I am white. The officials said to me, 'We maintain a policy of apartheid even though we know you don't — we will never put you with them.' It's a very bitter thing. We lived together, we cooked for each other, but we couldn't be in prison together.ii

I remember a prison officer on more than one occasion saying, 'Nelson Mandela, we can dislike, but we can respect him for fighting for his people—after all, Afrikaners have stood and fought for Afrikaners. But you, with everything in front of you that white society could give you, you're a traitor—we hate you.' And by God, they hated me.

But I didn't regret those days in prison. I'll tell you why. When we were taken to prison, the armed struggle was new. We were amateurs, we did what we could. I think we changed the course of South African history, and it was important to do that at that time. And when the armed struggle was started, we knew that one day that regime could be toppled. We didn't know when — they looked so solidly in power, so self-confident. Well, they're now ripe to be toppled, it's going to happen. That's why it was worth it: it was necessary to do it, and we did it because it had to be done.”

DENIS GOLDBERG, tasked by the Umkhonto we Sizwe High Command to develop weaponry for sabotage

The inevitable turn to illegality and violence in response to the banning of the legal organizations prompted further repressive legislation. The state was obsessed by a white-led conspiracy, premised on the racist conviction that blacks cannot organize without white leadership. It was mainly whites who were hit by the first house arrests and banning orders, the Congress of Democrats and the white-edited New Age that were banned. Whites were also over-represented in the first detentions under a new law that allowed people to be held without trial, in solitary confinement, for periods of up to ninety days.

John Vorster, the new Minister of Justice, has promised drastic action. Accordingly, the cabinet is discussing legislation to limit the freedom of speech and movement of 'agitators'. As has happened in the past, it can be done by confining a person to a certain area, or town, or even to his house.The form of house arrest which was used during the war was that a person was allowed only to go to his work, but in the evenings and at weekends he had to stay at home. Although the legislation is aimed at all 'agitators', it is intended primarily for whites. They are the most dangerous and the state knows who they are.

Sondagblad (Afrikaans Sunday newspaper), 22 October 1961

While the ANC was waging guerrilla warfare through underground Umkhonto cells, the PAC and its militant wing, Poqo, attempted a kind of spontaneous mass uprising. Although the government worried about the non-racial ANC because 'it has many more white brains at its disposal',ii the anti-white Poqo alarmed public more, especially after crowds of Poqo supporters killed several whites in incidents in Paarl and Transkei in late 1962 and early 1963.

Poqo's efforts — seemingly unaffected by the lessons of failed armed revolts throughout the history of African resistance iii — were easily crushed. The knockout blow to the PAC came when the boasts of its acting leader, Potlako Leballo, from neighbouring Basutoland (now Lesotho) led to raids that netted extensive membership lists, resulting in massive arrests of PAC supporters inside South Africa and the continued detention of its president, Robert Sobukwe.iv

The ANC tells the people straight: the struggle that will free us is a long, hard job. Do not be deceived by men who talk big with no thought for tomorrow.Freedom is not just a matter of strong words. It is no good to think in terms of impis [Zulu military units] and not of modern guerrilla war. PAC leaders like Leballo talk of revolution but do not work out how to make revolution. War needs careful plans. War is not a gesture of defiance. For a sum total of nine whites killed — only one of them a policeman, and he killed by accident —hundreds of Poqos are in jail serving thousands of years imprisonment.

Don't mistake the real target. Poqo is said to have killed five white road-builders in the Transkei recently. There are more effective ways of busting the white supremacy state. Instead, smashed railway lines, damaged pylons carrying electricity across the country, bombed-out petrol dumps cut Prime Minister Verwoerd off from his power and leave him helpless. And these acts are only the beginning.

Why make enemies of our allies? The Leballos spurn men of other races.We say that just as Africans bear the brunt of oppression under the white state, so will the white state be broken by the main force of African people.But this is no reason, we say, to reject comrades of other races whom we know are ready to fight with us, suffer, and if need be, die.

Find a way — but not the Leballo way. Umkhonto we Sizwe, army of the liberation movement, is for activists. We have struck against the white state more than 70 times (boldly, yet methodically). We are trained and practised.We shall be more so. We attack PAC-Leballo policy not out of petty rivalry but because it takes us back, not forward along the freedom road. Genuine freedom-fighters must find a way to fight together, in unity, in unbreakable strength. There is room in the freedom struggle for all brave men — and women. With your support we will win.

The ANC Spearheads Revolution — Leballo? No!’, ANC leaflet, 4 May 1963

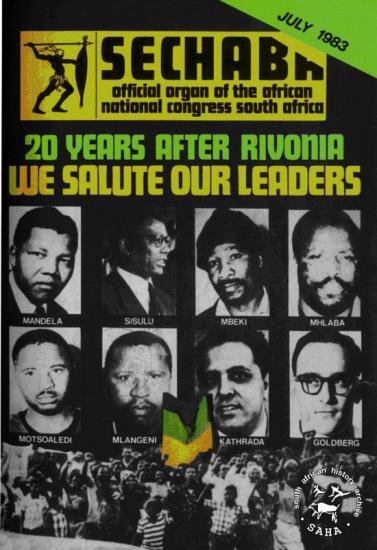

The ANC's military campaign was far more effective than the PAC's but soon it, too, was smashed. In mid-1963, police raided the secret headquarters of the Umkhonto we Sizwe High Command in a wealthy white suburb of Johannesburg called Rivonia. For Nelson Mandela, the first accused in the `Rivonia Trial', it was an unrivalled opportunity to explain the historical development of his movement's ideology and practice. Mandela laid special emphasis on two much-misunderstood issues: non-racialism and alleged communist influence.

The ideological creed of the ANC is, and always has been, the creed of African nationalism. It is not the concept of African nationalism expressed in the cry, 'Drive the white man into the sea!' The African nationalism for which the ANC stands is the concept of freedom and fulfilment for the African people in their own land.

The most important political document ever adopted by the ANC is the Freedom Charter. It is by no means a blueprint for a socialist state. It calls for redistribution, but not nationalization, of land; it provides for nationalization of mines, banks and monopoly industry, because big monopolies are owned by one race only, and without such nationalization, racial domination would be perpetuated, despite the spread of political power...The ANC has never at any period of its history advocated a revolutionary change in the economic structure of the country, nor has it, to the best of my recollection, ever condemned capitalist society…

…The ANC, unlike the Communist Party, admitted Africans only as members. Its chief goal was and is for the African people to win unity and full political rights. The Communist Party's main aim, on the other hand,was to remove the capitalists and to replace them with a working class government. The Communist Party sought to emphasize class distinctions, whilst the ANC seeks to harmonize them. This is a vital distinction.

It is true that there has often been close cooperation between the ANC and the Communist Party. But cooperation is merely proof of a common goal — in this case, the removal of white supremacy — and is not proof of a complete community of interests…I joined the ANC in 1944, and in my younger days I held the view that the policy of admitting communists to the ANC, and the close cooperation which existed at times on specific issues between the ANC and the Communist Party would lead to a watering down of the concept of African nationalism. At that stage I was a member of the African National Congress Youth League, and was one of a group which moved for the expulsion of communists from the ANC.

This proposal was heavily defeated. Amongst those who voted against the proposal were some of the most conservative sections of African political opinion. They defended the policy on the ground that from its inception the ANC was formed and built up, not as a political party with one school of political thought, but as a parliament of the African people, accommodating people of various political convictions, all united by the common goal of national liberation. I was eventually won over to this point of view and have upheld it ever since.

It is perhaps difficult for white South Africans, with an ingrained prejudice against communism, to understand why experienced African politicians so readily accepted communists as their friends. But to us the reason is obvious. Theoretical differences amongst those fighting against oppression is a luxury we cannot afford at this stage. What is more, for many decades’ communists were the only political group in South Africa who were prepared to treat Africans as human beings and their equals, who were prepared to eat with us, talk with us, live with us and work with us. They were the only political group which was prepared to work with the Africans for the attainment of political rights and a stake in society.

Because of this there are many Africans who today tend to equate freedom with communism. They are supported in this belief by a legislature which brands all exponents of democratic government and African freedom as communists, and bans many of them (who are not communists) under the Suppression of Communism Act. Although I have never been a member of the Communist Party…I myself have been banned and imprisoned under that Act.

It is not only in internal politics that we count communists as amongst those who support our cause. In the international field, communist countries have always come to our aid…Although there is a universal condemnation of apartheid, the communist bloc speaks out against it with a louder voice than most of the white world. In these circumstances, it would take a brash young politician, such as I was in 1949, to proclaim that the communists are our enemies.

I now turn to my own position…I have always regarded myself, in the first place, as an African patriot…Today I am attracted to the idea of a classless society, an attraction which springs in part from Marxist reading and in part from my admiration of the structure and organization of early African societies in this country. The land, then the main means of production, belonged to the tribe. There were no rich or poor and there was no exploitation.

It is true…that I have been influenced by Marxist thought, but this is also true of many of the leaders of the new independent states. Such widely different persons as Gandhi, Nehru, Nkrumah and Nasser all acknowledge this fact. We all accept the need for some form of socialism to enable our people to catch up with the advanced countries of this world and to overcome their legacy of extreme poverty. But this does not mean we are Marxists...I have been influenced in my thinking by both West and East…

…Basically, we fight against two features which are the hallmarks of African life in South Africa and which are entrenched by legislation which we seek to have repealed. These features are poverty and lack of human dignity, and we do not need communists or so-called 'agitators' to teach us about these things...Above all, we want political rights, because without them our disabilities will be permanent. I know this sounds revolutionary to the whites in this country, because the majority of voters will be Africans. This makes the white man fear democracy.

But this fear cannot be allowed to stand in the way of the only solution which will guarantee racial harmony and freedom for all. It is not true that the enfranchisement of all will result in racial domination. Political division based on colour is entirely artificial, and when it disappears so will the domination of one colour group by another. The ANC has spent half a century fighting against racialism. When it triumphs it will not change that policy…

…During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.

NELSON MANDELA, Statement from the dock, 20 April 1964

After making that statement Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment, along with Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Ahmed Kathrada, Raymond Mhlaba, Andrew Mlangeni, Elias Motsoaledi and Denis Goldberg.

After making that statement Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment, along with Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Ahmed Kathrada, Raymond Mhlaba, Andrew Mlangeni, Elias Motsoaledi and Denis Goldberg.

With most of the rest of the ANC's leadership also imprisoned, banned or exiled, anti-apartheid resistance waned, and thus began a period that has come to be known as 'the lull'.

DOWNLOAD CHAPTER 11 AS A PDF

NOTES

iBlack political prisoners were sent to Robben Island, the maximum security prison off the Cape coast, while whites went to Pretoria Central Prison. Racial segregation in South Africa's prisons has been repeatedly criticized, most recently by warders at Pollsmoor Prison (where most of the key ANC leaders were moved from the Island) who formed the Police and Prisons Civil Rights Union (Poperu). 'There is no white crime or black crime,' said a Poperu member, 'Why aren't all offenders treated the same?' Upon his release from Pretoria Central in 1989, a white ANC member, Roland Hunter, made a public call for black and white prisoners to be jailed together.

iiPrime Minister Vorster, quoted in Hansard, House of Assembly, 12 June 1963.

iiiThe last desperate armed uprising against white domination before the 1960 Pondoland unrest was Zulu Chief Bambata's battle against government troops in 1906, in which the chief and more than 500 of his warriors were killed.

ivUnder the 90-day act legislation of 1963, Sobukwe's three-year prison term then due to expire was extended (though with special privileges); many observers concluded that the continued sidelining of Sobukwe was at least a partial goal of Leballo's bravado. Sobukwe was not released until May 1969, when he was restricted to Kimberley, where he remained until his death in 1978.