In case you missed it, on Wednesday 27 November 2013, President Jacob Zuma signed into law the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI).

In case you missed it, on Wednesday 27 November 2013, President Jacob Zuma signed into law the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI).

History

POPI was first drafted in 2004 and it has undergone many changes since then. The then Bill was first tabled in Parliament in 2009 and since then it has been sent to and fro between the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces. In August 2013 the National Assembly finally sent it to President Zuma for signing. Although the Act was Gazetted on November 27, its commencement date is yet to be set.

Purpose

The Protection of Personal Information Act aims to:

"...promote the protection of personal information processed by public and private bodies; to introduce information protection principles so as to establish minimum requirements for the processing of personal information; to provide for the establishment of an Information Protection Regulator; to provide for the issuing of codes of conduct; to provide for the rights of persons regarding unsolicited electronic communications and automated decision making; to regulate the flow of personal information across the borders of the Republic; and to provide for matters connected therewith."

Catch 22

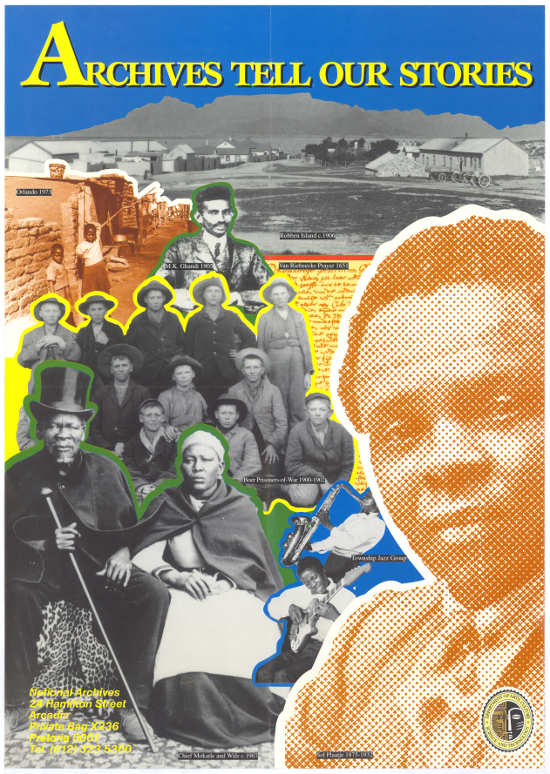

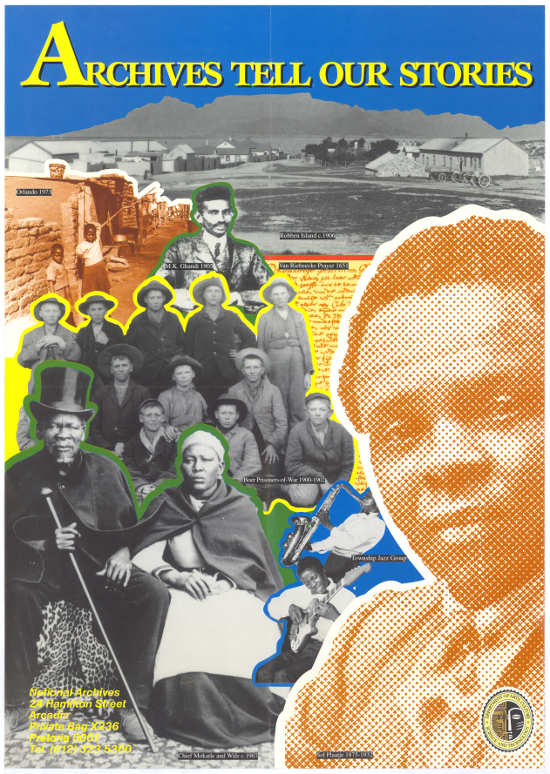

Although notably promoting the protection of personal information, POPI has very negative implications for all archival organisations such as SAHA which collect, preserve and use personal information for historical, statistical or research purposes.

While businesses will be required to review and amend their record keeping, employment and information technology policies and procedures in order to ensure compliance with POPI, archival institutions face additional challenges specific to their role in keeping historical records. These challenges include archivist having to go through all records released to them to ensure that no unlawful personal information is contained. This exercise alone will not only be time consuming but it will require more financial resources to be invested in the processing of archive collections.

In 2012 SAHA reported that if the now Act were to be passed it would create an "onerous burden for the archives". For instance, if SAHA establishes that a collection is lawful it may then only process the personal information if it has the consent of the individual or can establish that in doing so it will be pursuing a legitimate interest of SAHA, again requiring an assessment of each record containing personal information. Similarly the same test will need to be applied each time anyone wishes to access a record containing personal information from SAHA's archive, including for non-commercial educational and research purposes.

If archives do not have consent of the persons concerned and if that information is not already publicly available, the possible impact on the archive and the public could be that important personal information and factual history that is of public interest could be lost forever.

And in 2009 the Nelson Mandela Foundation together with SAHA submitted to the Portfolio Committee on Justice and Constitutional Development that there needed to be an exemption for "information processed for historical, statistical or research purposes". Unfortunately this argument which was in a previous draft has been ignored.

The Act is skewed towards better protecting personal information held by marketing and credit providers and does not entirely consider the implication of certain personal information processed through archives for mainly historical, statistical, non-commercial or research purposes. It is now up to the archival community to assess proactively how best to respond to POPIA in practical terms.

In case you missed it, on Wednesday 27 November 2013, President Jacob Zuma signed into law the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI).

In case you missed it, on Wednesday 27 November 2013, President Jacob Zuma signed into law the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPI).