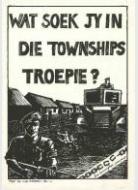

The anti-conscription movement predated the End Conscription Campaign, but it was this organized collective that helped popularise the cause of white conscripts. After all, conscription was "the only real aspect of apartheid that (was) a real imposition for the white community."1 According to Laurie Nathan, National Organizer in 1985, "people are only prepared to make this kind of sacrifice if they believe it is worth it... the fact that over 7000 national servicemen failed to report for duty (is) an indication of the large numbers who feel it isn't worth it."2 The ECC was unique. It gave a platform for people to express their rage, in an otherwise repressive environment. Ex-conscripts returned from the Borders with stories of their horrific experiences. Some returned with broken spirits. Some simply never returned. ECC representatives tried to remain objective and disaffected in the public forum, even if their own activism was motivated by personal experiences of serving in the armed forces they now refused to associate with.

Occasionally the impact of SADF conscription was overwhelming:

"SPEAK OUT SPEAK OUT SPEAK OUT SPEAK OUT SPEAK OUT SPEAK OUT SPEAK OUT

END CONSCRIPTION NOW

NO MORE SUICIDE!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!"3

By the 7th of March 1986, the destructive influence of compulsory military service upon otherwise apolitical white South Africans was unavoidable in public debate. On this day, the "astonishing" suicide figure of 74 over 30 months was released in parliament. The ECC publicity officer argued that South Africa could not "afford to lose so many young men through conscription."4 The CO Support Group was "at a bit of a loss as to what to do" over the high number of suicides reported.5 The call objecting to conscription needed to grow. There was only so much peer-led support groups could do.

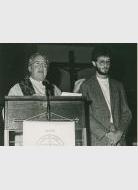

Laurie Nathan, head of the ECC, often had to deal with pessimism from within the movement, especially amongst organizers. He saw "the pudding" of his work "at all times remaining jolly and enthusiastic, and trying to inspire and motivate others."6 Coordinating events at a national scale was not an easy task. Not all events were successful, but Nathan consistently assured members that each event contributed to ECC work and development, and that an "honest and self-critical assessment was necessary."7

The ECC was made up of students and young people. Faced with explaining why a Cape Town Festival organizing meeting had been so unsuccessful, Nathan acknowledged that this was being held on the "eve of the Easter long weekend when people's minds were more on letting rip" than on the agenda of the meeting.8 Nathan argued that the anti-conscription movement had to place more thought

"on the building of a really broad anti-war consciousness...beyond the members...beyond even the people who we mobilize through concerts and public meetings, there are many many others who are influenced by the ECC."9

These men did not always know the exact mandate of the ECC, neither did they necessarily have strong convictions on other political issues - but they were all unwilling to serve "in what they perceive(d) as apartheid's army..."10 The result was a growing anti-establishment body representing a new voice of opposition.

Setting the scene for change

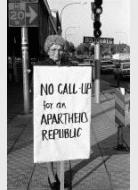

Once the ECC began to gain ground, its activities became more inclusive of different elements of the white community, in an attempt to provide a broad platform for discourse around issues of war, conscription and apartheid's injustices.

Politics

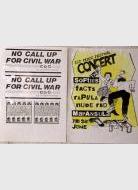

The ECC functioned as a dispenser of information, particularly once it launched its campaign around alternative service, which had been central to its mandate since its inception. The evolution of this campaign, with more solid solutions being discussed for alternative national service, allowed for more solid links across civil society, strengthening the anti-conscription movement.

Members promoted and organised public debates and discussions amongst the white left wing. Most memorable was the public debate between David Webster, Wits academic, and Van Zyl Slabbert, leader of the official opposition. This was later described as comprising of a "generally constructive" discussion about conscription, although Slabbert described the ECC as being "dangerously naïve, romantic, simplistic and counterproductive."11 In spite of this, ECC national organizer Laurie Nathan argued that there was no reason for the relationship between the two groups "to be antagonistic."12

Community

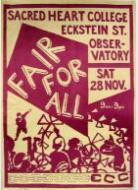

The ECC was not only engaged in helping those facing military service. The seemingly apolitical nature of some ECC events reflects how much the general community was absorbed into the movement through fun runs, school fairs, school concerts, and a host of other inter-racial, family-oriented get-togethers. Otherwise hapless mothers, fathers, teachers, sisters and friends now had a way of voicing their anti-war sentiment - and, ultimately, their anti-apartheid views.

Culture

"Hurrah! Hurrah!"13

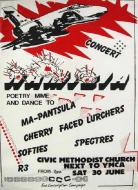

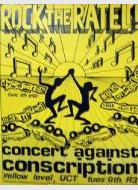

The 1985 Peace Festival was to be the centre piece of the ‘Working for a Just Peace' campaign. It was held to be held in Johannesburg in late June 1985. There would be a variety of activities including key-note speakers, panel discussions, workshops, COSG therapy sessions and an anti-war concert. Its impact was also anticipated in light of the July call-up.14 The aim of the event was to popularize the struggle against conscription and "put ECC on the map in Johannesburg."15

"(It was) without doubt one of the most exciting developments in Southern Africa for a long time!!?! Literally millions of peace-loving people throughout the world will be focusing on the role of the SADF and the question of conscription in South Africa at the time of our Festival. It will not be at all surprising if on the 7th of July the SADF lays down its arms."16

The 1985 Peace Festival represented a new ideological synergy of expression in art, thought and music. It saw the convergence of people and ideas in a forum driven by the desire for peaceful alternatives to the current repressive regime. Still, Nathan's initial excitement for the Peace Festival did not cloud his judgement when he admitted that the event had "never succeeded in attracting the Joburg (sic) general public."17 Problems were often unavoidable - including the refusal of a Visa to Cardinal Arns of Brazil, who had been featured in the festival programming as a key-note speaker.18

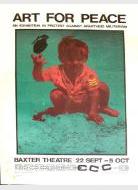

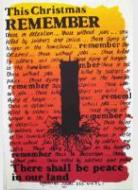

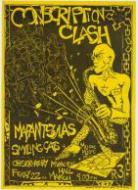

The Peace Festival presented only one slice in a medley of cultural events aimed at piquing the interest of a newly conscientized urban elite. This included film festivals, art exhibitions and poetry readings. Even the posters of the ECC became increasingly stylistic, using more nuanced political and cultural references.

Music

The alternative music scene's hold over popular culture at this point could be attributed to the influence of the anti-conscription movement. Lloyd Ross, musical custodian and the face of Shifty Records, has described the scene as including some of the "most vital and deeply honest music ever made" in South Africa.19

The music movement known as Voëlvry had emerged out of a generation of rock alternative English and Afrikaans speakers. For them, the music and literature of this rich, profound generation of cultural expression provided a collective call against a regime which sought to implicate them, white men, as perpetrators of its repression.

Names that emerged out of this period included Johannes Kerkorrel (Ralph Rabie), Koos Kombuis (Andre Letoit) and Bernoldus Niemand (James Phillips). The music that they created was often subversive; several albums were banned by the state. One of the most direct attacks against the National Party government was Koos Kombuis's track ‘Swart September,' which parodied the national anthem, ‘Die Stem.'

"...oor ons afgebrande skole (Over our burnt-down schools)

Met die kreun van honger kinders (With the groans of hungry children)

Dis die stem van al die squatters (it's the call of all the squatters)

Van ons land, Azania. (Of our land, Azania)"20

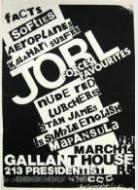

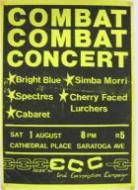

Shifty Records had been started by Lloyd Ross, who "simply could not comprehend how a music so compelling could be so utterly ignored by the music industry at large."21 Shifty represented bands like Sankomota and Corporal Punishment, but its main contribution to the ECC was in the compilation of Forces Favourites, a collection of bands who had played at ECC concerts and emulated the voice of a new mind-set of South African alternative rock music.22 Some of the songs were already recorded, some bands approached Shifty to record, and "some adapted their songs especially."23 The album was marketed to serve both a local and international sub-genre of rock ‘n roll that strongly connected with the struggle against the apartheid regime in South Africa. This included, amongst others, Cherry Faced Lurchers, The Softies, Jennifer Ferguson, Stan James, Roger Lucy, The Aeroplanes, The Facts and Kalahari Surfers.

Andrew Beattie reviewed the album for the Star newspaper, describing it as an "expression of concern about the current situation, the responsibility of white youth, alienation as a result of apartheid and concern about the future."24 A member of The Softies defended the ECC's fight against conscription, which was a "root destruction of basic human freedom."25 Another reviewer, Nigel Wrench, pointed out that this was the first time that local bands had "put their music where their politics is."26

Not all cultural forms of expression took on the same angry, punk-influenced sound and tone. Many established artists, including Johnny Clegg, Alan Paton, Andrew Buckland, Nadine Gordimer, amongst others, produced short stories (including a collection entitled ‘Forces Favourites), books and poems which spoke directly to the injustice inherent in conscription, as a part of a broader struggle against apartheid. Paton's 1979 ‘Caprivi Lament', written in response to the report of the death of several SADF conscripts (including black soldiers) in border incursions, became an anthem for Conscientious Objectors such as Peter Moll, who quoted him in letters from prison. The poem reflected the poignancy and sense of hopelessness evinced in the war, while at the same time fundamentally questioning its underlying motive.

"...was it South Africa you fought for?

Which of our nations did you die for?

Or did you die for my parliament

And its thousand immutable laws?

Did you forgive us all our trespasses

In that moment of dying

...is that what you died for, my brothers?

Or is it true what they say

That you were led into ambush?"27

The social influence of the ECC on white mainstream culture was profound. It was a catalyst in achieving a critical mass of creative outpouring that contributed towards the forging of a new white identity, whose ideological underpinning was both radical and unapologetic.

References

1 ‘Organising to stop the call-up,' Interview with Laurie Nathan, Objector March-April, 1985, v. 3. No. 1, South African History Archive (SAHA), AL2457 - The Original SAHA Collection, E6.4.5

2 Ibid.

3 Press Release, ‘No More Suicide' Annemarie Rademeyer, 7 March 1986. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.2.1

4 Ibid.

5 Minutes of COSG meeting, 1 August, 1986. South African History Archive (SAHA), AL2457 - The Original SAHA Collection, E6.4.2.2.

6 ECC National Organizer's Report to National Conference, January 1986. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6 8.1.6

7 ECC National Organizer's Report to ECC, CT, 1985. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6.8.1.3

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Letter from Laurie Nathan (no specified recipient) re: public debate Webster vs. Slabbert, Undated. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.1

12 Ibid.

13 ECC National Organizer's Report to ECC, Johannesburg, 19 March, 1985. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6 8.1.2

14 Letter from Peace Festival Committee (Laurie Nathan, Anita Kromberg and Richard Steele) to Bill Johnston, Episcopal Churchmen, 11 April, 1985. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.1.2

15 ECC National Organizer's Annual Report, 1985. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6.8.1.7

16 ECC National Organizer's Report, 1985. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6.8.1.7

17 ECC National Organizer's Report to ECC Johannesburg, 9 November 1985. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6.8.1.7

18 Ibid.

19 Lloyd Ross, Shifty Stories Part 1, Shifty Vault, Shifty Records

20 Koos Kombuis, 'Swart September', quoted in O'Leary, Derrick. 'The Border between Sanity and Insanity: the effects of the Border Wars on white South African society,' unpublished Honours thesis, Department of History, University of the Witwatersrand, p. 37

21 Lloyd Ross, Shifty Stories Part 1, Shifty Vault, Shifty Records

22 ECC National Organizer's Report, Johannesburg, 1985. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6.8.1.7

23 Ibid.

24 Andrew Beattie, Review of 'Forces Favourites', Star, 9 December 1985, Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6.8.1.7

25 Ibid.

26 Nigel Wrench, Review of 'Forces Favourites', 1985, Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6.8.1.7

27 Alan Paton, Caprivi Lament, quoted by Peter Moll in the 'Excerpts from an open letter', dated 19th October 1979, by Peter Moll (in which he again refuses to attend military camp) addressed to the officer commanding, Cape Flats Commando, Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.1.1