"My friends", he said, "we've reached our goal

the threat is under firm control

As long as peace and order reign

I'll be damned if I can see a reason to explain

Why the fear and the fire and the guns remain."1

*"Where militarism rules, truth is always the first casualty."2

Background

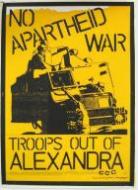

By the mid-1980s, South Africa was in flames, with violent resistance and escalating insurgence from all borders, including the ones inside the country. Rural uprisings in the desiccated countryside of South Africa's Bantustan homelands were met by violent demonstrations within the sprawls of South Africa's peri-urban townships.

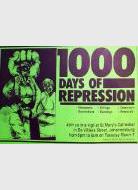

The state's response was to declare a state of emergency, something usually declared when the welfare of a nation is so threatened by "war, invasion, general insurrection, disorder, natural disaster" that such a declaration is deemed "necessary to restore peace and order."3 It gave the President of South Africa the ability to rule by decree, to heighten the powers of both SADF and SAP, and to restrict and censor any reportage of political unrest. The constant state of low-level siege experienced throughout this decade was divided by two such ‘declarations.'

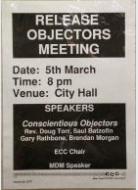

These two periods were central in determining the ideological and strategic direction of the End Conscription Campaign, and also had serious implications for the personal and professional lives of many ECC members. Even before the first declaration of a State of Emergency, members faced intensive bouts of harassment - meetings were regularly disrupted by hecklers who "booed and hissed and clapped" in an attempt to dissuade those involved.4

Entering a State of Emergency

"Greetings from a sunny state of emergency!"5

The first State of Emergency was declared on 20 July 1985, initially covering the Eastern Cape and the Pretoria-Witwatersrand-Vaal (PWV) area. Thousands were detained. A few months later, the State of Emergency was extended to the Western Cape. Declared soon after the Peace Festival, it effectively stifled the activities of the ECC in Johannesburg. During this time, ECC members were regularly harassed and often arrested. On July 30 1985, Clare Verbeeck, the head of the Johannesburg ECC, was interrogated. Her home was searched, with many documents being confiscated. Sylvia Brett, another active member, was raided in her home. The following month, several other members were detained, including Gavin Evans and Ian Moll.

September brought more raids on members, including Anne McKay, Anne-Marie Rademeyer - and again on Verbeeck. Security police were clearly unsettled by the existence of the ECC movement, which had split the borders between black and white resistance, and even more unnerved by how "little knowledge" they had of "the workings of JHB ECC."6 In December 1986, a print-run of 1987 ECC diaries waiting for collection at the printers was seized by the Security Police, with no reason given.7

In Cape Town attendance figures were down, but the generally self-sufficient centre was able to keep up spirits, and considered the numbers of attendees "good considering the fact that the white South African public have been very frightened...and as a result can not be relied on to come forward in large numbers."8

The ECC had to contend with having its name dragged through the mud in the public forum. Growing its name in the media inevitably meant confronting endless swathes of disinformation and misrepresentation, smearing the name of the ECC.

In August 1985 the Sunday Times reported that the ECC had been "launched to prepare the way for revolution."9 The Citizen quoted Adriaan Vlok deriding the ECC for "being used by the ANC to further its goals."10 Magnus Malan defended the role of troops in the townships and accused the ECC of "aiming to break down law and order by weakening the state machinery."11

Preparing for the Next Emergency

Reporting on the impact of the first State of Emergency, the Johannesburg annual report highlighted the "defiant spirit" that developed among the movement of active members, confirming their convictions "in deciding to continue operating."12 The State of Emergency had forced the Johannesburg ECC (and probably others) to "re-examine and democratise" its leadership, as there existed a "real possibility of leadership being taken away."13 Early the following year, Laurie Nathan admitted his feelings of having "too high a profile" in the ECC.14

There was clearly the need for flatter structures of leadership so that activities could continue no matter who got detained. There was also a need for political training and serious introspection. The second half of the 1980s saw increasingly repressive measures being sanctioned across the board of South African society. The need for the ECC to focus on securing and strengthening itself shows how much difficulty the ECC experienced in securing its existence by this stage.

The success of the ECC could no longer be measured by the success of its campaigns, but rather by its ongoing ability to endure and survive. Repression was increasingly severe, and on the 1st of May 1989, ECC founder member David Webster was assassinated by the notorious Civil Cooperation Bureau. (CCB)

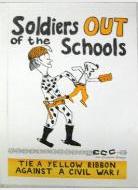

The laws around conscription had only become more oppressive, and the troops had not left the townships, with between 500 and 800 troops present in the townships between 1987 and 1988 at fourteen temporary military bases near so-called ‘unrest areas' at a cost of R5.7 million.15

But the ECC leadership urged members not to see this as a failure, but rather a call for more dissent. Conscription was still in place. Clare Verbeeck, as new National Organizer in 1987, argued that their task was "to unite that dissent into a powerful movement to change the law which forces men to participate in apartheid's wars inside and outside our country."16 Clare acknowledged that the State of Emergency had been "relatively successful in limiting a sense of national unity in ECC.

She wrote:

"We are fighting back..."17

One powerful campaign that was introduced in-between the States of Emergency was the ‘Alternative Service Campaign.' This was popularized by a number of developments in South Africa, namely the precipitation of a ‘brain drain' which was having a "retarding effect on the economy," as well as an ongoing moral commitment to end conscription.18 A statement by 33 Jewish conscientious objectors declared that there were "very limited options open to those opposed to conscription."18 In June 1988, immediately before the declaration of the second State of Emergency, the ECC met with the SADF in Pretoria, presenting them with a proposal for alternative national service.19

Second State of Emergency

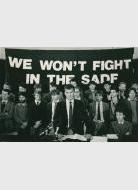

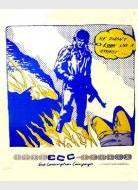

Unlike the 1985 State of Emergency, the second declaration was implemented on a nation-wide level. The press was now completely restricted from covering political unrest. The anti-conscription movement, including COSG, recognized that it needed to "clarify" its role in the new political context.20 This new milieu made it necessary for the ECC to adjust its priorities. It was increasingly difficult for the ECC to "overcome the effects of the State of Emergency."21 For the organisation to survive, activists needed to be "disciplined and well trained."22

As a result, political training and development were prioritized.23 Some of these new methods, necessary under the State of Emergency, put additional demands on activists, as there was far "more emphasis on alliance politics, front building, consultation and networking."24 ECC branches had also grown on campuses, and Verbeeck argued that these were significant. Campus branches of the ECC, replete with "young intellectuals, with few responsibilities, all physically in one place", were more likely to "withstand repression."25 On the 22 August 1988, Magnus Malan gave a press statement which effectively prohibited the ECC from continuing activity. Malan argued that

"(in spite of ECC's) attempts to create an impression of political neutrality... it (was) not difficult to see the organization's role in the revolutionary onslaught in South Africa."26

The ECC was seen to pose a danger to the

"safety of the public, the maintenance of the public order and the termination of the State of Emergency."27

The banning order was issued before the ECC had a chance to defend itself through a hearing or any other way. The ECC took no immediate action because it seemed pointless to challenge the restriction,

"in the light of court decisions at the time... since the truth or otherwise of...allegations would not have been at issue, but merely whether... (The Minister of Law and Order) had followed a technically ‘correct' process."28

Members of the ECC regarded the banning order as "nothing more than the opportunistic silencing of an embarrassing opponent," but there was little that could be done at this stage. 29

The army ain't what it used to be...

The tense atmosphere created during the initial declaration did not dissipate, even after restrictions were lifted. Banning orders on organisations such as the ECC had not been lifted. Despite lifting restrictions on media the Defence Act still limited publication of data related to the SADF. Max du Preez of Vrye Weekblad was charged under the Emergency Regulations for subverting the SADF in a 1988 news article.

The NP government was no longer able to rely as much on the burgeoning SADF to secure its position of authority, and by the early 1990s the armed forces began to turn conscripts away - in one instant, over 2000 - because it did not have the capacity to cope with the intake, leading one writer in Objector to state, with glee, that "the army ain't what it used to be."30

Covert anti-conscription activity

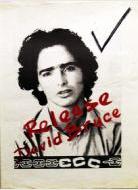

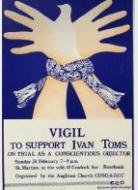

Despite the restriction order, public support for Conscientious Objectors such as Charles Bester and David Bruce was indefatigable. After the prison sentence for COs was extended to six years, their imprisonment took on new significance. Support for them was great, as they represented the spirit of a movement that had been shot down by ever-more repressive state forces.

"In this land of civil war

And walls set out between our

Hearts

No one is free

But some dream of freedom

While others build fortresses...

You kicked out your own brick

In the fortifications

(for that they lock you away)

But you let a shaft of future in

A glimpse of days still to break

Break, break the walls down."31

In a widely distributed statement, hundreds of groups and individuals called for an end to the restrictions placed on the End Conscription Campaign.32 This included a cross-section of prominent and popular individuals across civil society, including the likes of Nadine Gordimer, Archbishop Dennis Hurley, Professor John Dugard, Des and Dawn Lindberg, Athol Fugard, Andre Brink, Professor Dennis Davis and Dr Frederick van Zyl Slabbert.

References

1 Lyrics from ‘Weeping' by Bright Blue, Composed by Heymann, Fox, Cohen, Cohen, recorded and released by Bright Blue in 1987

2 Reverend Peter Storey, quoted in anti-militarization pamphlet ‘Must I do Cadets at School? A Guide for scholars and their parents', Grahamstown Advice Centre on National Service /Conscription (GRACONS). Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A7.5

3 State of Emergency Bill, B52D-97, Minister of Justice, 1997

4 ECC National Organiser's Report on ECC, Port Elizabeth, 20 April 1985. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6 8.1.4

5 Letter from David Shandler, to Matt Meyer, War Resisters League, 18 September 1986. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.2.2

6 ECC National Organizer's Report to National Conference, January 1986. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6 8.1.7

7 Letter from D. de Villiers, ECC, to Commissioner of Police, 12 February 1987. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.3.

8 Letter from David Shandler, ECC, to Matt Meyer, War Resisters League, 18 September, 1986. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.2.2.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 ECC Johannesburg Annual Report, 1985. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6 8.1.7.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 'Troops still in the Townships', Objector, April-May 1990, p. 15. South African History Archive (SAHA), AL2457 - The Original SAHA Collection, E6.4.5

16 National Organizer's Report to Johannesburg ECC December 1987. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6 8.1.7

17 Ibid.

18 Letter from Martin Birtwhistle, Durban ECC Lobbying Group, to Friends of ECC, 11 July, 1988. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A7.7

19 National Jewish Conscientious Objectors Statement, signed by 33 Jewish conscientious objectors, in Johannesburg and Cape Town, 21 September 1989. South African History Archive (SAHA), AL2457 - The Original SAHA Collection, E6.4.

20 Ibid.

21 Agenda Proposal, COSG National Conference, March 1989. South African History Archive (SAHA), AL2457 - The Original SAHA Collection, E6.4.2.10

22 Report on National Employees and Structure, 1988. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A6.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Press Statement (banning the ECC), Ministry of Law and Order, Cape Town, 22 August 1988. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.4

28 Ibid.

29 Letter from C. de Villiers, Acting Chairman (Johannesburg), for: End Conscription Campaign, to the Minister of Law and Order, 17 August 1989. Historical Papers, University of the Witwatersrand, AG1977 - End Conscription Campaign, A4.5

30 Ibid.

31 ‘Longlive flat feet: longleave', Objector, April-May 1990, (back page). South African History Archive (SAHA), AL2457 - The Original SAHA Collection, E6.4.5.

32 Peter Rule, ‘Poem for David Bruce', Objector, August 1989. South African History Archive (SAHA), AL2457 - The Original SAHA Collection, E6.4.5.