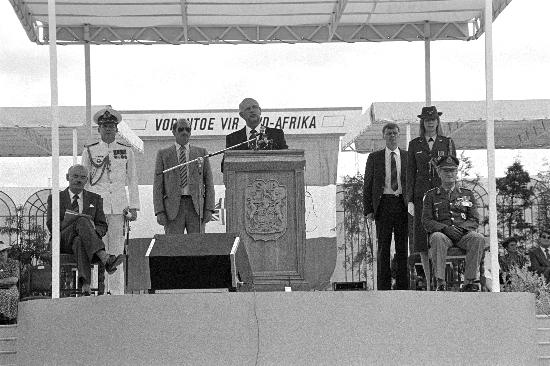

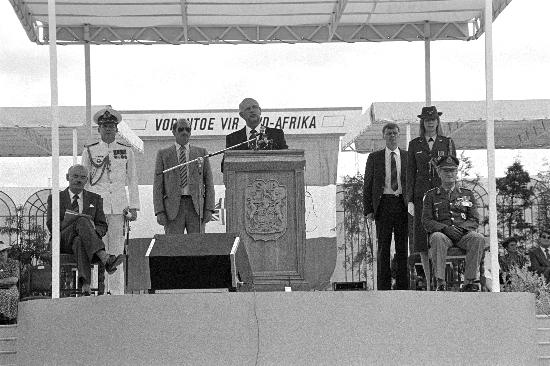

By the late 1980s, South African State President P.W. Botha had realised that sustaining the burgeoning system of apartheid was untenable, in spite of emergency regulations first implemented in 1985. Botha finally relented to the global call to end apartheid in 1989 when, on 5 July, he secretly met with Robben Island prisoner, Nelson Mandela.

By the late 1980s, South African State President P.W. Botha had realised that sustaining the burgeoning system of apartheid was untenable, in spite of emergency regulations first implemented in 1985. Botha finally relented to the global call to end apartheid in 1989 when, on 5 July, he secretly met with Robben Island prisoner, Nelson Mandela.

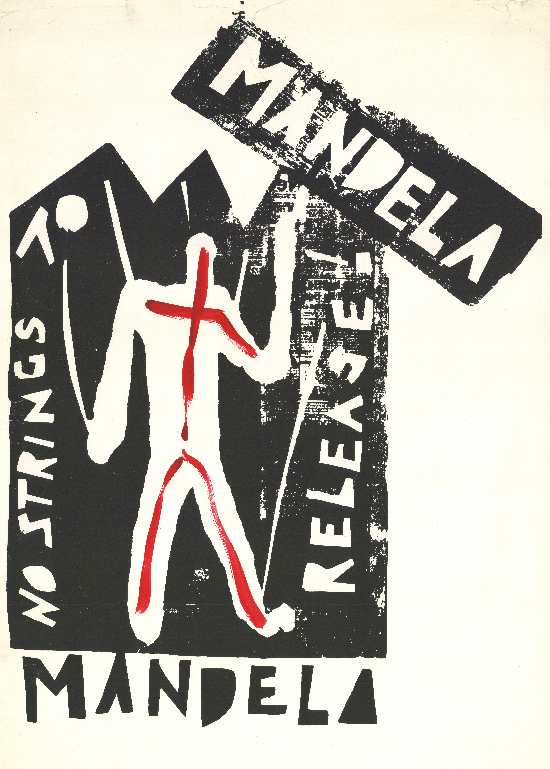

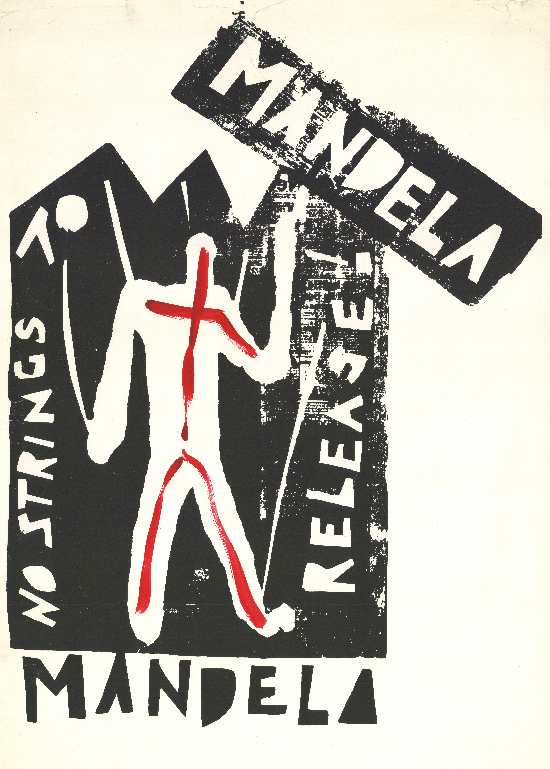

Mandela arrived at Tuynhuys, the presidential residence, in his personal capacity, donning a suit for the first time since the Rivonia Trial. Before arriving, Mandela laid out the potential road map to negotiations in ‘The Mandela Document,' addressing blockages to negotiations. He saw his task as being a "very limited one... to bring the country's two major political bodies to the negotiating table."

Mandela saw his role as merely emblematic of the anti-apartheid movement's willingness to negotiate with the state, but at this delicate time in South African history, such symbols were significant.

Breaking the ice

Mandela and Botha sat in each other's company and spoke. Decades of political division were symbolically laid to rest when Botha poured the tea for Mandela - a gesture unfathomable under the apartheid regime. The moment passed, and Mandela went back to prison. Within a month, Botha had left office, ousted by his own party, and replaced by the savvier negotiator, F.W. De Klerk.

Mandela's primary concern was getting the NP-led government and the ANC in exile to the official negotiating table, but secret international meetings had been taking place between white South African businessmen and representatives of the banned ANC, SACP and PAC since at least 1987. These included clandestine discussions through Cuban interlocuters in Lusaka, as well as the Dakar Conference, organised by the Institute for a Democratic Alternative (IDASA). The secret meetings laid down the ground work for later negotiations between the NP and the ANC, including CODESA 1 and 2, the Groote Schuur Minute, the Pretoria Minute, and the Multiparty Negotiating Forum (MPNF), which ratified an Interim Constitution in late 1993, paving the way for South Africa's first democratic election on 27 April 1994.

The legacy of 'Die Krokodil'

The legacy of 'Die Krokodil'

Botha's legacy is not one of being a negotiator - rather, it is one of tyrant, the overseer of death squads - but there was a flicker of redemption when he sat with Mandela at Tuynhuys. He has remained a controversial figure in the post-apartheid period; he refused to apply for amnesty at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), in spite of allegations linking him to covert hit squad operations. Botha outlined his conception of reconciliation in a letter written to TRC chairperson Archbishop Desmond Tutu in 1996, based on the historical example of the Treaty of Vereeniging:

"Reconciliation was achieved by closing the book on the past and focusing on the challenges of the future in unity, rather than reopening the wounds of painful experiences of the past..."

In concluding his 11-page letter, Botha defended his decision not to apply for amnesty at the TRC:

"I have in the past and will in future cooperate to achieve real reconciliation in our country, but there should be no doubt about my position regarding the following: I am not guilty of any deed for which I should apologise or ask for amnesty. I therefore for have no intention of doing this..."

Read the full text of the Mandela Document.

See the Dakar Declaration, signed after the 1987 Dakar Conference.

Related SAHA collections on the TRC

Reflecting SAHA's commitment to justice and accountability in South Africa, SAHA has actively collected archival materials relating to the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

Visit SAHA's TRC collections.

Many of these collections came to be housed at SAHA through the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Archives Project, a joint archival project undertaken by SAHA and Historical Papers at Wits between 2003 - 2006.

For information on other archives housing materials relating to the South African TRC, please consult the TRC Archival Audit Report.

In a project funded by the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, SAHA, in conjunction with the Race and Values Directorate of the Department of Education, is producing complete sets of the 78 Special Report television programmes on South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) to be used for educational purposes in South Africa.

This unique resource will be distributed free of charge to tertiary educational establishments in 2010. It will also be distributed to institutions working in the field of transitional justice and reconciliation, particularly those working with victim / survivor groups.

Learn more about the TRC Special Report Multimedia Project.

The Freedom of Information Programme (FOIP) collection comprises copies of materials released pursuant to the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA). The collection includes apartheid era security establishment records, documents created by the South African government bodies and agencies post- apartheid, and documents from several private bodies. It also contains documentation of the collection process.This collection contains correspondence from P.W. Botha to Archbishop Desmond Tutu on his view on the TRC process, under AL2878_A2.4.1.10. Normal 0 false false false EN-US X-NONE X-NONE

By the late 1980s, South African State President P.W. Botha had realised that sustaining the burgeoning system of apartheid was untenable, in spite of emergency regulations first implemented in 1985. Botha finally relented to the global call to end apartheid in 1989 when, on 5 July, he secretly met with Robben Island prisoner, Nelson Mandela.

By the late 1980s, South African State President P.W. Botha had realised that sustaining the burgeoning system of apartheid was untenable, in spite of emergency regulations first implemented in 1985. Botha finally relented to the global call to end apartheid in 1989 when, on 5 July, he secretly met with Robben Island prisoner, Nelson Mandela. The legacy of 'Die Krokodil'

The legacy of 'Die Krokodil'