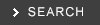

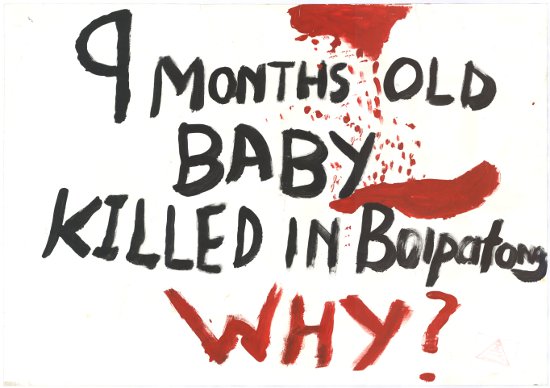

Over 40 people were killed in the Boipatong Massacre on 17 June 1992, a township near Vanderbijlpark in Gauteng. The massacre was the culmination of ongoing political violence in the area which rocked the township and put a halt to negotiations as African National Congress (ANC) member blamed the National Party (NP) for the attacks.

Many of the victims were women and children caught in the crossfire of political violence. One woman explained how her sister in-law came knocking on her door hysterically with a baby on her back: “I could hear her children crying from the shack next door. I opened the door and she fell on the floor. She was stabbed and chopped on her neck. She died there on the floor.”

Another resident explained how she watched her mother die when they were attacked in her home “My mother woke up, I followed her. We were afraid. After that I hid under the bed. I heard the men say they want ANC members”. The grieving woman explained that her mother had been undressed by the men and they stabbed her to death.

The Boipatong massacre is remembered as one of the most brutal moments of violence, when 200 men from Kwa Madala an Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) hostel went on a rampage through the township. Armed and said to be supported by the apartheid state they looted, vandalised houses and hacked people to death whom they believed to be ANC supporters. ANC comrades responded in kind by burning the homes of police and IFP members.

The incident at Boipatong was endemic of the violence that had engulfed South Africa between the mid-80s and early 90s between United Democratic Front (UDF)/ANC supporters and Inkatha (later IFP) supporters. The Boipatong massacre placed a spotlight on the Reef area and the IFP hostels. Most of the violence during this period stemmed from the hostels and the neighbouring townships in retaliatory attacks.

Most recollections of the massacre explain the attack as an attempt by the National Party to undermine the ANC ahead of the first democratic elections. De Klerk and the nationalist security forces complicity in the violence had not been established by the Goldstone Commission. However, police response to the violence had been slow. The Commission also appointed a British criminalist who discovered that police had not gathered any fingerprints, blood samples or any other evidence that could be used to convict perpetrators of the violence.

See inventory for Barbara Hogan Collection AL3013

See inventory for The Brain Currin Collection AL3065

See inventory for Mark Gevisser's Research Papers for Thabo Mbeki: The Dream Deferred AL3284

See inventory for The Lawyers for Human Rights (LHR) Collection AL3183

See inventory for The Sunday Times Heritage Project (STHP) Collection AL3282

See inventory for The SAHA poster Collection AL2446