The past weeks, following the news coverage on the public broadcaster's decision to bar coverage and broadcasting of any public protests, raises questions about the role of a public broadcaster. Today society cannot be imagined

without mass media. In many ways, public opinion and social awareness are all largely shaped by television, radio, newspapers and the internet. They act as a medium which we constantly re-visit to develop collective attitudes on public affairs and establish communal actions towards certain issues.

The decision to restrict the broadcasting of protest images poses two problems. Firstly it is quite reminiscent of the Apartheid era where media was censored and used against the people, secondly, it violates the right to access of information.

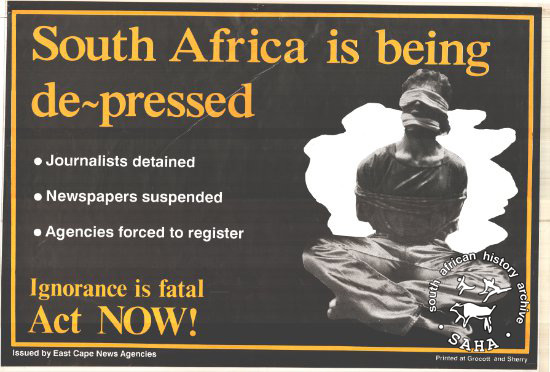

In the past and today, albeit under a different guise, media has been used a political tool to manipulate, silence, erase and oppress. This was the case in 1985 when President P.W. Botha announced a State of Emergency in thirty-six districts of South Africa. Under this condition, the National Party could implement its apartheid policies such as the detaining of hundreds under and for unconstitutional reasons, unlawful killing of political activists behind the facade of neutralising political dissent, and the imposed media restrictions on the emergency coverage.

These restrictions prevented both national and international reporting on the unjust conditions that were imposed by the apartheid regime. Therefore contravening people's right to access of information and by extension hindering any progress to resist the discriminatory laws. Why this is relevant and how is this similar to post-apartheid South Africa you ask?

Through the Struggle for Justice Programme, SAHA has been involved in the preservation and creating of access to archival collections that document the struggle for justice in South Africa and the continued efforts of building a democracy. Although the programme focuses on documents of the past specifically, it is the recording of the continuing struggles in the making of a democracy that I'm particularly interested in.

Thirty-one years later South Africa is an independent country still hurdling the challenges of improving socio-economic inclusion and strengthening its democracy. However, feelings of exclusion and erasure are still as pervasive. Communities that find themselves in the peripheries of economic hubs constantly need to display rage in response to the structural violence they experience. At the heart of the matter is belonging. If communities have their issues relegated to the margins, they are as good as erased in the public discourse, more especially in discussions of creating a national identity.

So what implications does media censorship have on the struggle for justice archives as well as freedom of expression and access to information? The process of archiving is a continuous one. Today we find ourselves faced with the task of building national cohesion off the fragmented pieces of the past. Fifty years from today, events happening today will constitute the archive of that time and if we are to manipulate or choose to erase the information made available the image created then will be just as fragmented. Lastly, post-apartheid South Africa is a multifaceted society with good and bad. Any medium that strives to present a flawless society falls into the trap of a-historicism and denies the people their right to information. The people should have the right to construct their own opinions about the country without manipulation.