In the late 1980s, in the face of increased opposition to forced removals, a 1982 government circular stated that removals would no longer be forced on communities who own their land.

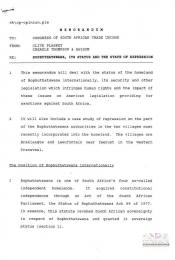

Instead, the Government resorted to using forced incorporation as much as possible, to consolidate as many ethnic groups as possible into the Bantustans or homelands. "Incorporation" referred to the process through which the South African government transferred black people and their land into the homelands through the redrawing of boundaries.

Incorporation was used to achieve the government's political aims of forcing blacks to live in their ethnically designated areas. This meant that these people became the responsibility of their so-called "homelands'' and the South African government was no longer responsible for seeing that their material and political aspirations were met. These people were robbed of South African citizenship and exposed to brutal homeland rule.

The fierce anger with which communities fought incorporation was directly related to their rejection of "the apartheid assumption that blacks should exercise their political rights in the Bantustans, as well as on direct experience of the material deprivation and repression that homeland residence means...Repression, corruption, poverty, an inhumane bureaucracy and loss of citizenship. These are the reasons that it is so vehemently opposed" ..

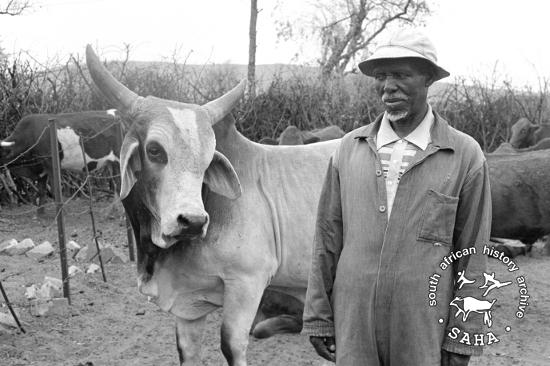

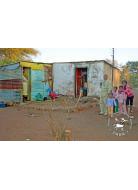

The farm Braklaagte, (the settlement or village is also referred to as Lekubung) situated 20km outside of Zeerust , in the Marico hills, on the road to Botswana, was bought in 1907 by members of the BahurutsebaMoilwa, a breakaway group under Israel Moilwa, who had settled in Leeuwfontein. Israel asked his brother Malebelele Sebogodi to be the headman of Braklaagte. In 1927, they bought a further piece of land, Welverdiend, (or Mosweu, as it is known in Setswana), as a cattle post, through missionaries signing the title deed. Several members of the tribe slowly settled at Mosweu, over the years.

One elderly member of the community, "Elsie" Tshegofatso Motsusi, remembers that her

ancestors lived in the area long before whites arrived:

"My mother's father was called Kete and all the Boers that come from other farms that are close to us- when they settled here my grandfather was already here. When I hear the elders talking, they say after the old man had passed on, we decided to come here in Lekubung because he was in the outskirts of this place."

In the early years, Braklaagte was a comfortable place to live:

"Those days we were really holding things together. We were milling the sorghum... There was no big village here. You see this big plot going there, and there and there and there. Those were fields. We tended the land there. We were milling ...sorghum, maize...you would find that your land was well kept..." (DipaleNtebele)

"It was a collective, because if Mme Senna had two cows and I had two cows and another lady had another two cows and the men who were at home would help us to farm with the cows but we combined them all and therefore this made it a collective and the other one would be watering the mielies and the beans...women worked together to remove the birds and ensure that the crops were taken care of and the birds did not eat the crops that were on the farm....When they are farming Mme Senna has her own farm and when they are done on her farm they would move to my farm and they would farm on my farm". "The parents were ploughing in the fields, they planted sorghum, mealie, beans, Letlhodi [peas], Tloo[Lentils ] we had enough food we were never hungry because of the ploughing". (Tshegofatso Motsusi)

(Tshegofatso also remembers the landowners lending fields to those who came after all the fields had been distributed).

"We ate food from the soil. We used to eat the food that was not fatty... There was no sickness as there was no clinic and people gave birth at home and children were breastfed and we ate healthy food ... We did not eat too much meat at all". (Florence Senna Mongake)

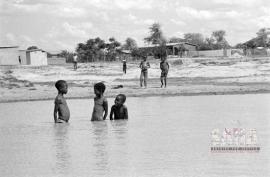

AL3274_D35.01_BRA_Children swimming at water hole

Children swimming at a water hole, Braklaagte, November 1986. (Photographer: Gille de Vlieg)

The Braklaagte community fought repeatedly to retain control of their land against government attempts to threaten its security and uproot its residents. Braklaagte successfully avoided forced removals in 1938, and again in 1958 under the leadership of Chief John Sebogodi, the successor to Malebelele. The tribe reports this, and it seems that John Sebogodi was a chief who could not be bribed or intimidated to move into the reserves, and later, Bophuthatswana. A regent, George Moilwa had been in place until the young John grew up.

He said, "I'm not going to sign. Can you see all these people? They own this land. I'm just an employee. They asked me to look after this land. Just like you, you can't tell me to herd your cattle and I then move them without your permission"(Tshegofatso Motsusi talking about John Sebogodi's response to the threat of removal).

The community found itself involved in resistance to the imposition of passes for women, and John Sebogodi's wife, Maria, was one of the women who led protests against this policy.Thus the couple were rooted in resistance to Apartheid policies.

Tshegofatso Motsusi remembers what happened in 1957:

"The women were like, "What I.D.'s? No ways! We are not men. We are not going to Mines, we don't take I.D.'s. Only men take the pass because they go to mines or Railway [now Spoornet]". They (Government officials) said, "You will take them whether you like it or not". The women then stood up and dispersed. They said "You can give those to your mothers". After the chief refused the removal and the women the passes, they were rounded up and jailed, and the chief and headmen brutally beaten."

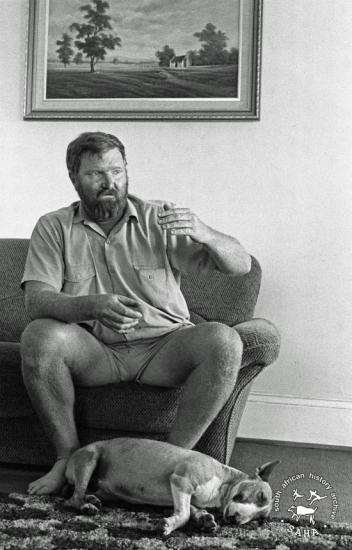

Charles Hooper , an Anglican priest based in Zeerust in the 1950s and 1960s, opposed Apartheid, and documented this terrible time of pass laws for women and attempts at forced removals in his book, "A Brief Authority" and George Bizos was one of the young lawyers who helped the community at this time. Hooper got the British Government to intervene and stop the removal in the 1950s, according to Tshegofatso:

"They got out of jail, so afterwards the forced removal issue disappeared because of

England. The Queen reprimanded them, and then it was quiet. It was then we relaxed.

We became friends with Charles and all that they helped us with ideas".

Florence Mongake and Tshegofatso Motsusi remember a time in the 1960s when the men of the village stopped ploughing and went to the mines, hoping to make money:

"The houses were built with sand and it was the white sand, not just any sand. It is specifically to build. It was cow dung, and my father used that and you will take it from the old buildings and you will make them look like bricks and you will make a house and I will look for grass and there were women that can make the thatch roof and the men would go and come back after 9 months and he would come back and find a house. When he left there was no house". (Florence Senna Mongake)

Tshegofatso Motsusi worked in Johannesburg and sent remittances home:

"It was getting better because my siblings were working. We would all send money, and in the meantime no one is ploughing. The ploughing fields are dying a slow death. By late 1960s they were no longer ploughing...The main reason was that men left women at home. [the men] left for greener pastures. Women are not strong enough to plough or follow up on cattles to plough. [Men]They went for Gold in Gauteng. They would live by the hostels; they would leave the wives and kids to starve."

In Johannesburg, many residents of Braklaagte, while working on the Reef, became politicised and joined the ANC. George Mokgosi remembers joining the ANC in the 1960s.

The reason for my joining was because of a friend of mine called Rantao, you see? He used to live in Dube (George Mokgosi)

Tshegofatso Motsusi also speaks of her motivation to join the ANC.

"Many youth in the community were anti-Mangope and the homelands."

Later, when a popularly recognised chief in the district, Abram Moilwa, was deposed and Lucas Mangope was instated, the resistance in this area was to flare up into violent confrontation. In the face of militant resistance by the Braklaagte community, the plans to remove them were left in abeyance. Mangope was to become president of the designated homeland for Tswana people, Bophuthatswana, and his wrath would be felt by the Braklaagte people, in time.

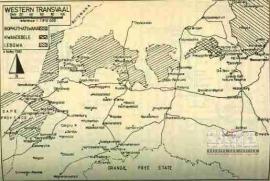

In 1976 when Bophuthatswana took independence, Leeuwfontein and Braklaagte, both owned by Bahurutse communities, were not part of it as they existed within a corridor of white-owned farms. However, a commission for the consolidation of homelands was formed under the Department of Cooperation and Development, and in the early 1980s, it investigated and planned that the Marico corridor should be added to the homeland, and that white farmers in this area should be bought out.

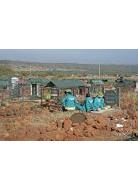

In 1983, the cattle post Mosweu, with its residents, was incorporated into Bophuthatswana. Although the people of Mosweu fell under the chief of Braklaagte, once they were in Bophuthatswana, a new headman, Edwin Moilwa was appointed by the Bophuthatswana authorities to govern the residents of this piece of land. The residents were not consulted and thus they rejected Edwin's authority. He started harassing them and confiscating property and exacting fines. He also appropriated a quarry that the Mosweu residents had traditionally had access to, for building houses, and prevented a company that offered to drill for water for the water- deprived community, from doing so.

These acts foreshadowed for the rest of the tribe, living at Braklaagte, what awaited them if they were incorporated.

As Tshegofatso Motsusi described, Mangope's men came and camped around Moilwa's house in the village:

"then after the trucks and cars from Mangope's office came and camped at his house - that is when he said, " I'm the chief, Sebogodi is nothing".

Towards the end of 1985 the Borders of Particular States Extension Amendment Bill was published, providing for incorporation of extra land into the independent Bantustans. Included in this Bill was the provision for the incorporation of Braklaagte and a neighbouring farm, Leeuwfontein, also settled by the Bahurutse, into Bophuthatswana.

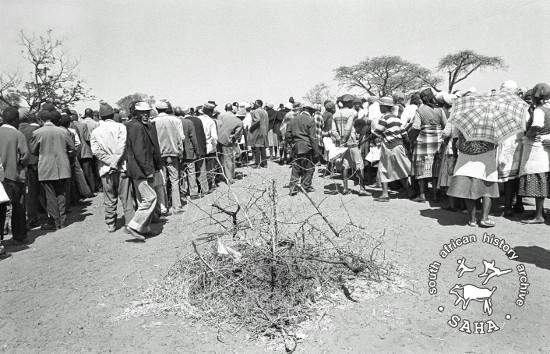

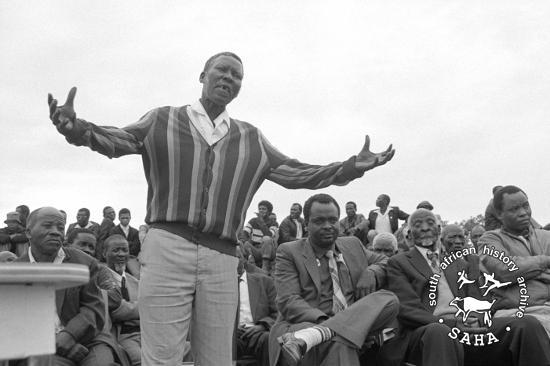

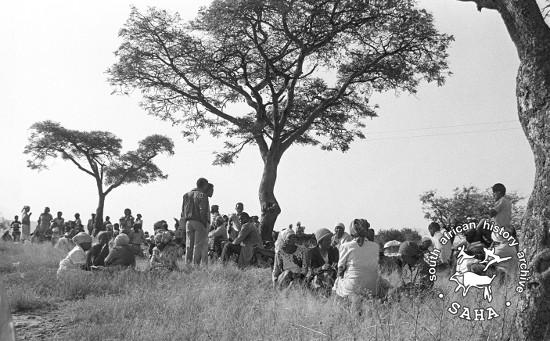

In July 1986, Braklaagte learned of a decision taken by the State to incorporate the community into the homeland of Bophuthatswana. The land deal had been negotiated between the South Africa government and the President of Bophuthatswana, without consultation or consent of the community concerned. A Zeerust commissioner and a Pretoria official presented the decision to the community as a fait accompli. The community responded angrily to the news of the planned incorporation.

A community meeting was called to discuss the crisis in September 1986. A petition rejecting incorporation was signed by over 3000 members of the community and sent to government, requesting urgent meetings.

Another Act was passed in 1986 that gave rights to black people living outside of the homelands. The Restoration of South Africa Citizenship Act was passed in 1986, for black people who had lived permanently outside the homeland.

It also applied to those residents of homelands had left the Bantustans before the date of independence and had been permanently resident in South Africa on 30 June 1986. Taking advantage of this Act, the community took the decision to have their South Africa citizenship restored, as further proof that they regarded themselves as citizens of South Africa and not Bophuthatswana. (All Tswana people in South Africa had originally lost their citizenship automatically in 1976 when the homeland took independence, but the 1986 Restoration of Citizenship Act was for the benefit of black South Africa urban dwellers that the apartheid government was trying to woo away from the UDF, in the apartheid reform era of the 1980s).

In spite of all these actions and requests for meetings, on December 31, 1988, the government gazette issued a proclamation officially incorporating Braklaagte into Bophuthatswana, thus, community members, with South African citizenship, found themselves at the mercy of President Mangope's regime. As South Africa citizens they would not have any right to access social and state services - they were aliens in an alien land, forced by the country of their birth into a no- man's land of limbo. The children of the community were now refused access to Zeerust schools in South Africa, and yet refused entry to Bophuthatswana schools as South Africa citizens.

On 19 May 1989, Lucas Mangope addressed a meeting at Leeuwfontein in which he made it clear that the Bophuthatswana regime did not intend to tolerate any opposition. He said...

"From today onwards you must stop your activities to oppose my government."... "Bophuthatswana is like a prickly pear. The same as a prickly pear, Bophuthatswana is very tasty, but it is also dangerous. I warn you strongly not to abuse me. If you do I will prick you and pierce you like a prickly pear. You must inform your children of this."

Under the leadership of acting chief, Ntjanyana (Pupsey) Sebogodi, Braklaagte challenged the incorporation in court but lost the case in March 1989. Pupils trying to bus to school in Zeerust were beaten by Bophuthatswana police in March 1989.

"They did a road block. There would be a road block there, kids would be offloaded from the bus, then went on to the bus one by one. They would be asked, "Who is your chief?" If you say It's Moilwa, "Get on", if it's Sebogodi," Voetsek! Get off"! The kids that said their chief is Sebogodi, they slept in jail." (Tshegofatso Motsusi)

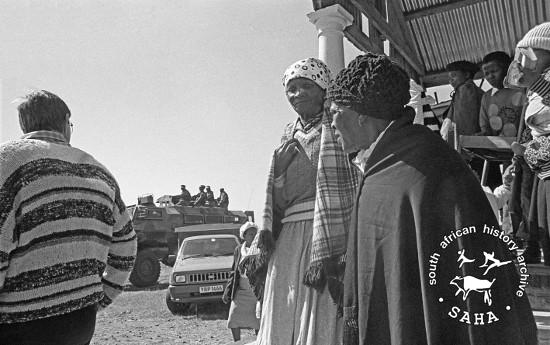

Police patrolled the village and teargas was fired at random. Skirmishes between the small pro incorporation group and anti-incorporation elements in the community took place and Pupsey Sebogodi and about one hundred of his followers were assaulted by Bophuthatswana police and detained or arrested.

Bophuthatswana police denied the latter the right to see their lawyers. By July, 34 more people had been arrested, including two 80 year old residents and a TRAC fieldworker. Journalists were also barred from entering the area. In the ensuing struggles, on neighbouring Leeufontein, where residents were also resisting incorporation, nine Bop police were killed, and at least two residents. TRAC and black Sash were banned in Bophuthatswana in July 1989.

"They [police and soldiers] camped here from 1989 to 1994 and they would beat people during this time. They were protecting him [Edwin Moilwa] and it was five years that they stayed here" (Florence Senna Mongake)

At this point in South Africa history, national events changed - in Feb 1990, the ANC was unbanned, and talks about talks began for a transitional government to issue in a new democratic South Africa, and yet the violence continued in this community.

On Dec 1990, a local branch of the ANC was launched in Braklaagte. This led to the violence intensifying, with teargas being fired by Bophuthatswana police, and pro- Bophuthatswana vigilantes attacking residents with knives and axes. Violence spilled over into Mosweu as well.

The people of Braklaagte continued to endure great harassment by the authorities, with over 5000 people being forced to seek refuge in churches in Zeerust in the township of Ikageng.

The few remaining residents in Braklaagte lived in fear. After winning their court appeal against incorporation in May 1991, the community finally returned to Braklaagte on Saturday 13 July 1991.

The tension and struggle over who ruled Braklaagte continued, influenced by the national political struggles for power at the time. A member of the Braklaagte community remembers Madiba coming to Zeerust and helping, and the ANC regional offices assisting at this time.

"And then it turned out that when it was Mandela's time that we called him here to

Zeerust. In all honesty it was he who did some good. That freed us up to back home to Lekubung. The conflict began and ended that way."(George Mokgosi)

Today Braklaagte residents do not do much farming. The farm implements lie rusting like monuments to a former time. Stands and plots have been rented or sold to newcomers.

According to Ntebele Dipale, Braklaagte today is not the good place that it was. He was born in Braklaagte in 1937. People used to grow and mill their own sorghum and maize. However, there have been other positive changes:

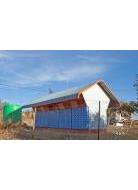

"The (apartheid) government did not help with anything. We would need to go and get our own water. The elders would also work on the chickens and the women and girls would go farming and there was no electricity and no water and we stayed for a long time with no electricity. I think we got the electricity in 1996". (Florence Senna Mongake)

"If I had a good fence I would love to plant some vegetables. Plant vegetables, give to the poor like me, give to the orphans, I think about those things but now I don't have a fence. The cattle's will just walk over and eat them. Now that thing that makes me think of ploughing fields"(Tshegofatso Motsusi)

"We look at things and we are living well and there are no problems. My yard had beans and everything else really so farming would still be done and I have my children and they also have children and the place is then reduced in this manner... so people would not farm anymore as much. If I were not too old I would be farming still." (Mmatika Modisakwana)

Ploughs and farm implements lie rusting around the chief's residence, further proof that the community has become a place of settlement rather than a place of residence and active farming.